Let me narrate two stories from the recent experience of science and maths in action.

Story 1:

In the last couple of months, on four different occasions, I observed something curious in restaurants. I found rice grains in the salt shakers. I hadn’t come across this earlier. Is it a common practice in restaurants? Is it a common practice among all restaurants and I happened to notice only in these particular ones? Is it that I noticed it in these places only because they have glass salt shakers that allowed me to observe the contents? I don’t know. All I know is I was excited to see this particular science concept in action.

As a chemist, I have used desiccants in the lab ranging from Calcium Chloride in drying tubes to molecular sieves in heavy water. A desiccant is a material that absorbs moisture from the surrounding atmosphere. It is a common sight in any chemistry lab.

In everyday life, however, I had seen it before only in the small bags of silica gel desiccant in new bags and backpacks. Seeing rice in the salt shaker was new to me and hence, the excitement. In my enthusiasm, I even asked the waitstaff in two of the restaurants as to the reason they had added rice grains to their salt shakers. In both instances, they told me that it helps the salt fall easily. I must admit I had a strong urge to sit them down and explain the chemistry behind it. It took some self-control and some gentle nudging from my husband to let go.

While the desiccant action of substances is quite simple and common, salt and rice grains are a special case. It so happens that both salt and rice grains are hygroscopic (substances that absorb moisture from the air around them). However, salt also dissolves in water. Therefore, when it absorbs enough moisture from the air, it can dissolve in that absorbed moisture and form clumps. Clumps in a salt shaker are extremely inconvenient. That is where rice grains come to the rescue. They absorb moisture from the air inside the container and since they don’t dissolve, they are dry themselves and also keep the salt dry and free-flowing. Not just rice grains, any pulses or even coffee beans have the same effect.

Although this is something I have noticed recently, apparently this is age-old grandmothers’ wisdom that’s been in practice for decades. In my experience, however, I have not seen it in Indian households since salt shakers aren’t that common in our homes.

Story 2:

Recently on vacation, I was at a rustic resort in a remote location near the historic town of Hampi. All around the resort are paddy fields and boulders, only near the entrance there are some rough tracks that function as roads to reach the main road leading towards the highways. In the morning after breakfast, we asked the resort staff directions to the river bank, from where we were to take a boat. The staff told us that we should turn right at the gate and follow the rough track road that skirted the paddy field right in front of the gate and continued along to join the road which led to the river bank. They also said we could save time by walking along a shorter track that cut across the paddy field.

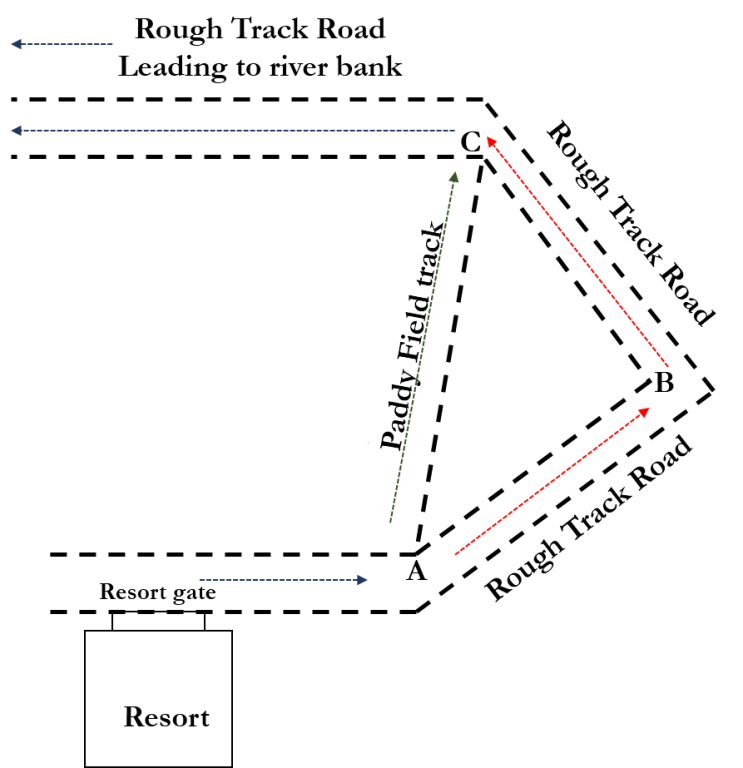

When we went to the gate, we could see the rough track road, the paddy fields and the track that cut across the paddy field. To our utter amusement and delight, we saw that the rough track road skirting the paddy fields formed two sides of a right-angled triangle and the track that cut across the paddy field formed the hypotenuse. So, essentially the staff had recommended us to take the hypotenuse that would be the shortest distance compared to the sum of the other two sides. A rough sketch below (Figure 1) shows the approximate layout.

Figure 1 – Layout of the tracks and roads around the resort

Again, I had a strong desire to explain the Pythagoras theorem to the resort staff. Thankfully, I listened to my husband, we followed the track across the paddy field, and reached the river bank.

On reflecting on these two instances, I started wondering whether it is more important to know the science or use the science. Does it matter that the staff at the restaurant and the resort did not know about the science and maths concepts behind their habits? I don’t think so. The fact that they have observed the benefit of this habit, follow it, and recommend it to others is itself the practice of science. On the other hand, my knowledge of the underlying concept gives me a personal satisfaction but is not a necessary condition to practise the science. It is, in fact, dangerous to know and not practise.

What concepts do you practise without knowing the mechanism behind them? What concepts do you know about and don’t practise? Food for thought.

Dr. Soumya Sreehari

Latest posts by Dr. Soumya Sreehari (see all)

- To drink water or not to drink – that is the question - 11 June 2021

- Puzzles for fun and learning - 28 May 2021

- A questioning mind is a thinking mind - 14 May 2021

- Play and learn having fun with words - 7 May 2021

- 4 lessons to learn from the Montessori method - 30 April 2021